Eduardo González

Thirty years ago, the government of Felipe Gonzalez took advantage of the major events of 1992 to develop a whole strategy of public diplomacy whose high point, from the political point of view, was the celebration in Madrid of the second Ibero-American Summit in the framework of the commemorations for the fifth centenary of the Discovery of America.

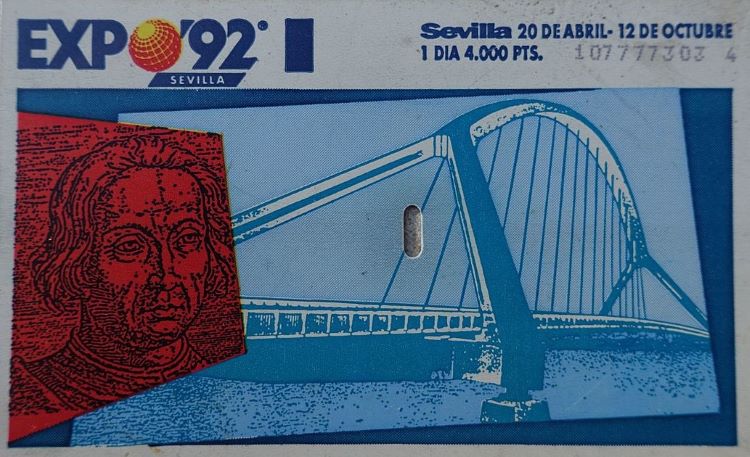

As Professor Julio Sanz López recalled, 1992 saw “the largest public diplomacy operation” ever known in Spain, “based mainly, although not exclusively, on the simultaneous organization of a large number of mega-events”, such as the Olympic Games in Barcelona, the Universal Exposition in Seville and Madrid as European City of Culture and, “in parallel”, in the implementation of other projects “essentially linked to the Commemoration of the fifth Centenary, such as the creation of the Cervantes Institute” and, of course, the second Ibero-American Summit of Heads of State and Government.

Precisely, the real unifying element of all this was the commemoration of the fifth centenary, which not only served the Government to promote “the knowledge and dissemination of the historical and current reality of modern and democratic Spain at world level” (Alto Patronato del V Centenario, July 29, 1991) but also to promote and disseminate the idea of the Ibero-American Community of Nations as a forum for dialogue and integration and with a view to the active incorporation of Europe into the Ibero-American problem.

The idea of commemorating the fifth centenary began in the early eighties, with the UCD government, which resulted in the creation, in 1981, of the National Commission for the Fifth Centenary. However, after some hesitant and inconclusive beginnings, the first signs of attention came in 1982, when the United States presented to the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) its candidacy to hold a Universal Exposition in Chicago in 1992 to commemorate the arrival of Christopher Columbus in America.

The American proposal served as an incentive for the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which immediately urged the National Commission for the 5th Centenary to study the possibility of holding an exposition in Spain in 1992 on the occasion of the fifth centenary. Once the idea was accepted, Spain presented to the BIE its own candidacy of Seville as the site of the Expo, in homage to the important role played by this city during the colonial era, but the hardest part was yet to come, and it was here that Spain deployed all its diplomacy.

The truth is that, from the beginning, everything pointed to a clear victory for the American candidacy. For this reason, the Spanish government launched an aggressive diplomatic offensive with the Ibero-American countries, through its ambassadors accredited in Madrid, in order to obtain their adhesion to the BIE and, with this, to obtain their vote in favor of a Spanish candidacy with a clearly Ibero-American vocation. In a very short time, the BIE received eleven new member states (Spain even paid for the entry of some countries), which made their debut at an assembly in which it was approved, as a reconciliatory formula, the holding of a joint exhibition in Seville and Chicago (although the U.S. candidacy was finally withdrawn in 1985). Thus, Felipe González, of the PSOE, found himself with a Universal Exposition and a National Commission for the V Centenary whose first steps had been taken by the UCD.

In any case, as the project matured, Spain introduced new elements to commemorate not only the fifth centenary, but also everything that represented the memory of 1492: the conquest of the kingdom of Granada, the expulsion of the Jews and the publication of Antonio de Nebrija’s Grammar, the first of the Castilian language and of any other vulgar language derived from Latin.

As if that were not enough, Spain and the Ibero-American countries took advantage of the atmosphere generated by the 5th Centenary celebrations to create their first common forum of understanding at the highest level. Between 1983 and 1992, up to ten conferences were held to prepare the ground, but the great step forward was taken in 1990, when, on the occasion of the signing of the treaty of friendship and cooperation between Mexico and Spain, the process for the creation of the Ibero-American Community of Nations was set in motion (the mere fact that the term “Ibero-American” was accepted was already a significant change), the first major step of which was the first Summit of Heads of State and Government.

According to the agreement adopted by all, the first Summit was to be held in Mexico in 1991 (in order to avoid suspicions about Spain’s role in the conquest) and the second in Spain in 1992. “In this way, the greatest initiative of multilateral diplomacy of Ibero-American character up to that date would arise in the heat of the 5th Centenary, overflowing to a great extent the traditional practical scope of a commemorative celebration”, highlights Julio Sanz López.

At that second Summit, held in the Spanish capital on July 23 and 24, 1992, the 21 heads of state and government approved a Madrid Declaration in which they defended “representative democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms,” reaffirmed the values of the United Nations in the face of the geopolitical change caused by the fall of the Soviet Union, supported the nuclear, chemical and biological arms limitation treaties, reaffirmed their commitment against drug trafficking and terrorism, and created a framework for cooperation and decision-making among the foreign ministers of the Member States through regular meetings.

Barcelona Olympic Games

The other major focus of 1992 was the Barcelona Olympic Games, whose importance for international diplomacy derives, above all, from the historical circumstances in which they were held: the first Games since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the USSR, the first participation of South Africa after 22 years excluded because of apartheid, the first Games without a threat of international boycott in many years (although there were fears of something similar after the first Gulf War and the possible Arab rejection of Israel’s intervention), the reconfiguration of the European map after the fall of the Berlin Wall (new independent countries and the unification of Germany) and the impact of the wars in Yugoslavia (the Serbs, Montenegrins and Macedonians participated without the Yugoslav flag, as individual athletes, while Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia were able to debut as independent states).

Under these circumstances, and under the impression of the Yugoslav wars, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) issued an appeal in Barcelona on July 21, 1992, in favor of the “Olympic Truce” (an old custom of the Olympic Games of antiquity, established in the 9th century BC), so that all States and all national and international organizations would suspend any armed conflict and intensify their efforts to achieve peace at least during the period of the Games, including the seven days preceding and following them.

The document was delivered in February 1993 by IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch to UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali. The Olympic Truce was approved by the UN General Assembly in October 1993, but, as expected, it was soon violated: in February 1994, during the XVII Olympic Winter Games in Lillehammer, a bombing of the Sarajevo market caused the death of almost 70 civilians.