The Diplomat

A report by the Alternativas Foundation recognises that the government of Pedro Sánchez has broken the traditional “active neutrality” maintained by Spain between Morocco and Algeria, in favour of Rabat.

The report was written by professors Alfonso Casani and Beatriz Tomé for the Foundation, which is close to the PSOE, and is entitled ‘Today’s Morocco and the Spain-Morocco-Algeria triangle in a context of triple crisis’.

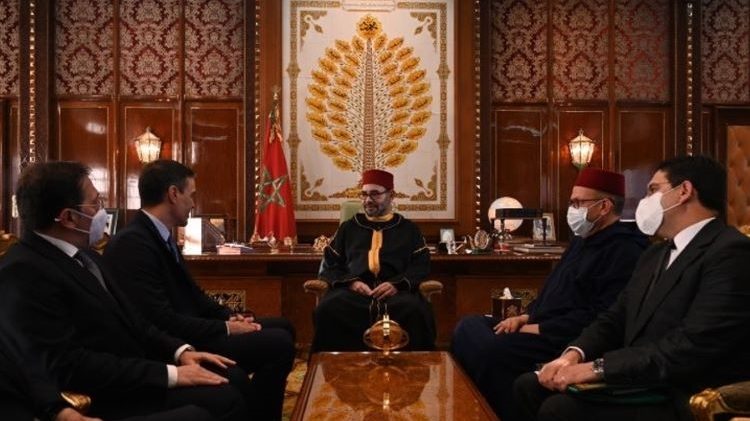

The text recalls that Spain’s relations with Morocco and Algeria have never been simple, creating a complicated triangle in which maintaining a balance and not provoking the anger of Rabat or Algiers was key. For this reason, he considers that the letter sent by the Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, to Mohammed VI in support of Morocco’s autonomy plan for the Sahara broke with the traditional ‘active neutrality’, characterised by the search for a balance that would allow energy interests to prevail with the former and migratory and security interests with the latter.

Sánchez’s letter pointed out that the Moroccan autonomy plan is ‘the most serious, credible and realistic basis’ for resolving the Sahara conflict, which, in the authors’ opinion, also generates new challenges that Spain will have to face, including the imminent EU Court ruling on trade agreements with Morocco.

The report considers that the government’s change of position, in addition to seeking an improvement in relations that would leave behind the crisis unleashed by the reception of the Polisario Front leader, Brahim Ghali, in Spain, “is motivated by an interest in reducing migratory pressure on the borders and by a desire to promote the perception of stability on Europe’s southern border vis-à-vis the EU in the face of instability on the eastern border”, reports Europa Press.

Moreover, it came at a time of growing assertiveness in Moroccan foreign policy and in which “the issue of Morocco’s territorial integrity is at the heart of its national, regional and international policy”. The recognition by the then US president, Donald Trump, of Moroccan sovereignty over the Sahara emboldened Rabat and has led the Alawi kingdom to try to get other countries to endorse this thesis.

Morocco’s return to the African Union in 2017 should also be interpreted in terms of the Sahara, with a view, according to the authors, to trying to influence the position of the organisation and its members in its favour and, ‘ultimately, to achieve the unlikely expulsion of SADR from the organisation’.

In reality, what Morocco wants with the addition of new support for its cause is to “legitimise the policy of fait accompli” in order to resolve the Sahara issue, which in turn makes it “unlikely” that there will be “progress on the multilateral path proposed by the United Nations”.

As a result of the letter, Spain and Morocco have embarked on a new stage in their relationship, which has had its maximum expression in the High Level Meeting (RAN) of 1 and 2 February. “This conciliation has not been free of concessions and continues to face elements of tension“, Casini and Tomé stress.

“The question of Morocco’s territorial integrity and its position towards Ceuta and Melilla continue to be a stumbling block in relations between Spain and Morocco”, they warn, stressing that “the pending opening of customs” with the two autonomous cities and “the migration issue translate these tensions on the ground”.

On the other hand, they draw attention to the fact that the foreseeable publication of the ruling by the EU Court of Justice on the trade agreements between the EU and Morocco before the end of the year, “which will surely exclude the territories of Western Sahara” from these agreements, will constitute “the first serious challenge” for Spain in this new stage, given that it will coincide with its rotating Presidency in the second half of the year.

“Despite Spain’s favourable stance towards Morocco, the ruling will force a renegotiation of trade agreements in a context marked by Morocco’s growing intransigence on this issue”, they warn. Rabat’s reaction, which has so far been fairly moderate in previous rulings, will certainly have an impact on Spain, given the trade ties between the two countries and the interests at stake.

As for Algeria, its reaction to Sánchez’s letter was the withdrawal of its ambassador from Madrid and three months later the suspension of the Friendship Treaty. Since then, it has chosen to favour ‘the Italian energy supply route to Europe over the Spanish one’ at a time when the EU is looking for alternatives to Russia as a supplier.

The authors consider that ‘in the short term, it is difficult to foresee a conciliation’ between the two countries given that ‘neither has made conciliatory gestures’. “The current energy crisis and Algeria’s revaluation as a gas and oil exporter strengthen its international position and allow us to foresee a greater assertiveness in its foreign policy”, say Casini and Tomé.

The report also devotes special attention to the regional situation and in particular to the non-existent relationship between Algeria and Morocco, which broke off diplomatic relations in August 2021. The authors frame it as ‘a dynamic of regional competition between the two countries and fluctuations in the perception of asymmetry or weakness that each has of the other’.

The two countries have tried to mediate in their troubled region, particularly in the conflicts in Libya and Mali, and have also recently taken their rivalry to the energy sphere. Trade opportunities for Algeria, a ‘traditional gas supplier’, have increased with the conflict in Ukraine, while Morocco is ‘advancing positions in the context of the energy transition’, as it seeks to become ‘Africa’s ‘green energy leader”.

The authors warn of “two black swans” on the horizon. First, “a possible scenario of popular revolt, a consequence of worsening living standards and the economic impact of successive crises”, referring to the COVID-19 pandemic and now the impact of the conflict in Ukraine, among others.

Although they see a replica of the protests that took place in 2011 in Morocco as “unlikely”, they warn that the country “faces widespread social discontent with the economic situation”. In this sense, they see a rise in social unrest as likely, but not at the national level, but at the local and regional level.

In the case of Algeria, “it has overcome with difficulty an important cycle of protests since 2019”, which led to a change of president and a new constitution, but there is also a risk of social unrest in the future. The reaction of both regimes, ‘already mired in a dynamic of democratic regression, would compromise relations with the EU (…) and could pose greater security pressures for Europe’.

The second would be the eventuality of a deterioration in the relationship between Morocco and Algeria leading to ‘a military conflict’ between the two. “Although unlikely, this would have a strong destabilising effect on the region, increasing an already latent arms race’ and further weakening the lack of integration in the Maghreb.