Eduardo González

“We are on the sixth of January / to sing and dance / to San Baltazar / This is your neighborhood / the Camba Cuá / San Baltazar.” This is one of the many candombes with which the residents of Camba Cuá, a central neighborhood of the Argentine city of Corrientes, pay homage every January 6 to King Balthazar, the patron saint of the “free and enslaved blacks” of Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay since colonial times.

As is known, the feast of the Magi coincides with the celebration of the first of the three Epiphanies of the Christian liturgical year, which symbolizes the revelation of Jesus to the pagan world, represented by the Magi. The first reference to the Magi from the East is found in the Gospel of St. Matthew, but no number, name or royal office is specified. It was not until the 6th century that the names of Melchior, Gaspar and Balthasar were recorded for the first time in a mosaic in the church of San Apolinar Nuovo, in Ravenna (Italy).

As time went by, and once the initial theological disputes over which should be the most important celebration of Christmas (Birth of Jesus or Epiphany) were overcome, the unification of the two led each country to choose one or the other date as the day par excellence for gifts. Most countries opted for Christmas Eve, but in Spain, where as in other Catholic countries Epiphany was unified with the feast of the Three Kings, the turning point came in the sixteenth century, when the Church banned the custom of distributing toys or sweets as a gift (a French feudal tradition of pagan origin) and established, in compensation, Easter as a symbol of the victory of the day over the night. From then on, the Kings of the East became inextricably associated with Christmas gifts.

The celebration of the Three Kings arrived in America aboard the ships that conquered and colonized the New World, and it is at this point that King Balthazar (or Baltazar, according to the transcriptions), the Black Magician King whom the African-American communities turned into their patron saint, assumes a special role.

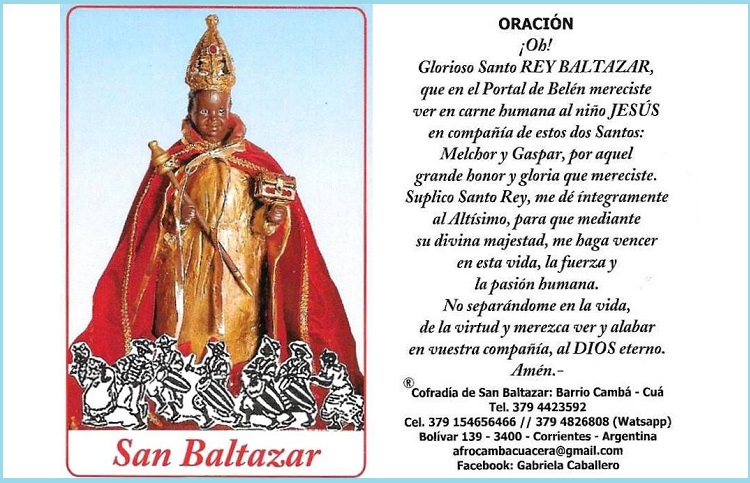

San Baltazar

San Baltasar, Santo Rey Baltasar or Santo Cambá (“black” in Guaraní language), who is represented in the processions with an upright appearance, crowned head and a chest in one hand and a scepter or sword in the other, is a saint of popular origin (in fact, he has not been canonized by the Catholic Church) very venerated, especially in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay.

In times of Spanish colonization, January 6 was a day of rest for slaves of African origin, especially in Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Mexico and Uruguay, which gave rise to the celebration of the “Pascua de los Negros” (Easter of the Blacks). However, the true antecedents of Saint Balthazar as patron of the Afro-descendant community (slave or free) began in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, especially in the Litoral (in the Argentine provinces of Corrientes, Santa Fe, Chaco and Formosa), where his cult has been documented at least since 1726.

As the scholar Gustavo Goldman states, the forced arrival of African slaves to the Spanish colonies generated the need to create forms of social and cultural integration of the newcomers and their descendants in order to avoid disturbances, and one of these formulas was the creation of religious brotherhoods for the “free and enslaved blacks”.

Thus, in 1772, the Cofradía de San Baltasar y Ánimas was created in Buenos Aires for “morenos, pardos e indios” (“browns and indians”), according to Professor Marcela Andruchow. Although it was dissolved barely a century later, the confraternity was the starting point for the extension of the cult of Baltasar in the Litoral, where it is still celebrated in Corrientes, Santa Fe, Formosa and Chaco, and is even celebrated by migrants from these provinces or from Paraguay in the Buenos Aires conurbation, despite the scarce presence of the black population in present-day Argentina (as anthropologist Norberto Pablo Cirio reports, the descendants of slaves came to represent 30% of the population of the Río de la Plata region, but by the end of the 19th century they barely reached 2% due to the wars and the yellow fever epidemic of 1871 in Buenos Aires).

In Corrientes, the feast of San Baltasar or Santo Cambá is celebrated from January 5 to 7 with dances of African influence (for which he is also known as “the Holy King of Candombe”) in the traditional Cambá Cuá Park (“Cave of Blacks “, in Guaraní), thanks to the tenacity of the current Cofradía de San Baltazar, composed of several families who gather at the hermitage of the Santo Negro to pay homage to their saint.

The other great focus of the cult of the Black King is Uruguay, where many slaves or former African slaves settled after 1743 and where in 1787 the Brotherhood of King Saint Baltazar of Montevideo was created, founded “by free blacks and slaves”, with the objective of indoctrinating, helping the brothers in their needs and organizing the religious processions on the day of their saint, January 6.

The veneration of the Saint Cambá arrived in Paraguay from Uruguay in 1820, when the liberator Jorge G. Artigas asked for asylum to José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (dictator and first Paraguayan president since 1814) accompanied by a group of 200 descendants of African slaves. The Afro-descendant community of Paraguay (made up of about 2,500 people gathered in about 300 families) still celebrates today the Kambá Kuá Festival (this year celebrated its seventeenth uninterrupted edition), in which ritual dances are danced and in which whites cannot participate and can only observe.

Curiously, the cult of Balthazar was also registered in the Metropolis itself, specifically in Seville, where between the 15th and 16th centuries an important African colony from slavery was concentrated (up to 8% of the total population). The first brotherhood for blacks in the city was confirmed at the end of the 14th century by the Pope, but the great boom came in the 16th century, when the authorities allowed up to thirty African dances during the Corpus Christi procession. In this context, the Africans of Seville also began to celebrate their own patronal feast during the Epiphany, dedicated, of course, to King Balthazar.