Eduardo González

On August 3, 1979, the then commander in chief of the Army of Equatorial Guinea, Teodoro Obiang Nguema, took up arms against President Francisco Macías Nguema (a member of his own clan, the Mongomo esangui).

It was the end of a dictatorship that had caused 50,000 political homicides, 10,000 disappeared and more than 150,000 exiles. The self-proclaimed “president for life” was shot on 30 September and Obiang has since become the longest-lived president in the world.

As journalist Juan María Calvo recalls in his book Equatorial Guinea: the lost opportunity, the then vice-chancellor of the Embassy, José Luis Pera (maximum representative of Spain, who had withdrawn his ambassador in 1977 because of the aggressive anti-Spanish rhetoric of Macias), received on August 1, 1979, in his house in Malabo, the unexpected visit of Obiang Nguema, who, “with a certain nervousness, looking back as if he feared someone was spying on him”, delivered three messages addressed to King Juan Carlos, the President of the Government, Adolfo Suárez, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Marcelino Oreja. “We can’t stand it anymore, this is the end, we have to try it now, we need your help…”, was the only thing he said.

Suspecting that this was an important matter, Pera decided to move the next day to Madrid to deliver the messages personally. Once in Spain, on August 3, he went to the Ministry’s headquarters in the Santa Cruz Palace, where he reported the facts to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Carlos Robles Piquer. When he decided to contact Marcelino Oreja (who was about to travel with Suárez to Brazil and Ecuador), no one in Madrid knew that the coup d’état had begun that very morning.

The sending of the three telegrams was recounted by Obiang Nguema himself in a testimony collected by the press cabinet of his party, the PDGE. “Long before the actions were taken against the dictatorial regime of Macias, I secretly appealed to the Spanish Government and announced what was going to happen through letters to the President of the Government, Mr. Adolfo Suarez, as well as to King Juan Carlos. The purpose of these letters was to request economic and military support to promote change”, he explained.

“I made this request for fear of a supposed reaction from the Soviet, Chinese and Korean civilian and military advisors who were in the service of the regime. I waited for the response for several days and, not receiving it, we decided to take risks and managed to reduce the enemy troops, a combat that lasted approximately two weeks”, he continued.

“Once success was achieved, the change came naturally and we took over the political leadership of the country. Congratulations began to come from all sides, internally and internationally. Foreign delegations began to arrive in Malabo, including the Spanish delegation, headed by the Director General of Foreign Policy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who informed me that the Spanish Parliament had rejected my proposal because the new Spanish democracy should not be involved in African conflicts and it was more prudent to remain neutral”, he added.

Days after the triumph of the so-called Freedom Coup, Obiang sent new telegrams to the King and Suarez in which he explained the events and requested, on behalf of the Military Council constituted after the uprising, “collaboration and support to the Spanish Government in its task of the democratic, economic and social reconstruction and restoration of Equatorial Guinea”.

Doubts about the role of Spain

Spain offered its support on 6 August, through the Spanish diplomatic delegation. On that day, Marcelino Oreja gave a press conference in Rio de Janeiro in which he congratulated the new Guinean regime and assured that Spain was “in the best disposition to give all the help that Guinea needs”.

Although Spain was the first country to recognise the new regime, Adolfo Suárez “emphatically” denied Spain’s participation in the coup d’état. “Spain does not intervene, does not prepare and does not execute any kind of coup d’état”, he declared in Brazil.

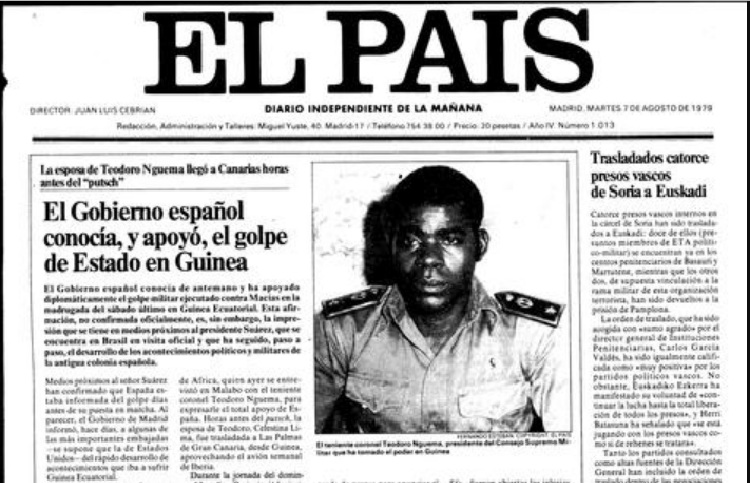

Despite this, the following day the newspaper El País published (four columns on the front page) that, according to “media close to President Suarez”, the Spanish government “knew beforehand” and had diplomatically supported the military coup against Macias, and even assured that the Spanish government had informed some important embassies -including that of the United States- of what was going to happen. Spain was followed by other countries in the recognition of the new regime: Gabon, Cameroon, the United States, France, Morocco (which sent a protection detachment), Nigeria and, significantly, the USSR and China.

The same newspaper stated, citing diplomatic sources, that a delegate from Obiang had gone to Madrid to present the coup plan to the government, that after his evaluation by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Suárez himself had given him the “green light” and that, hours before the uprising, Oniang’s second wife, Celestina Lima, had been transferred to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria from Guinea taking advantage of Iberia’s weekly plane.

In December 1979, Juan Carlos I made an official visit to Malabo which was returned by Obiang in the spring of 1980. Likewise, in October of that same year, both countries signed a treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, which allowed the creation of joint ventures in the sectors of hydrocarbons, minerals, banking and transportation.

Nevertheless, tensions between the two countries reappeared. On the one hand, Madrid accused Obiang of not advancing towards democracy and of not confronting the poverty of the population, while the Guinean president denounced the welcome in Spain of political opponents in exile. The spark exploded in May 1983, when, in the height of Obiang’s personalist dictatorship, the Spanish Embassy gave protection to a soldier whom the regime accused of conspiracy. After this first diplomatic crisis, Equatorial Guinea gradually moved closer to the Franco-African economic area.