Eduardo González

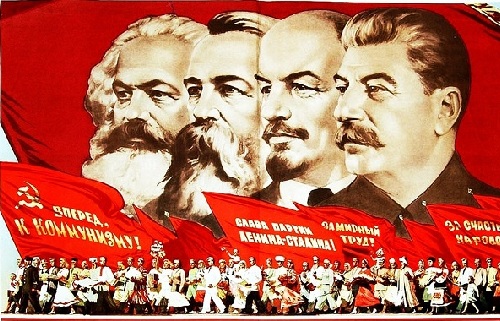

In 1933, the Stalin regime decided to interrupt the publication of the complete works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The break came precisely when it was going to publish a small and unknown text of Marx on European diplomacy in the eighteenth century in which exposed a history of Czarist Russia that, surprisingly, did not match the official canon established by Stalinism.

Between August 1856 and April 1857, Marx serially wrote a series of articles in the London newspaper The Free Press in which, from letters and pamphlets from the British Library, he analyzed the loss of United Kingdom hegemony in the Baltic in favor of Russia.

In the articles, later collected in the book Revelations on the history of diplomacy in the eighteenth century, Marx revealed that the British diplomats themselves were very surprised by the way in which their country, without any shame, systematically violated the treaties signed with their allies. An example of this was the unilateral breach of the treaties with Sweden in favor of a common enemy of both countries, Russia, which thanks to this managed to impose itself as a hegemonic power in the Baltic.

Probably Stalin would not have had any problems until this point of the story, but things got complicated with the controversial fifth chapter of the book, in which Marx tried to explain how “that phantom of power” that was Czarist Russia had been able to reach such dimensions and become an obsession for the European Courts.

Marx’s starting point was simple: Russia (more precisely, the Principality of Muscovy), which managed to free itself in the fifteenth century from the domination of the Mughals, had learned from its former tyrants -whom it had served “by representing the traditional role of the slave who acts like a lord”- the way to subjugate the other Russian peoples under his yoke, and then spread to the Baltic and the Pacific.

The strategy, learned from the “abject school of Mughal slavery” and continued by both the princes of Muscovy and the Russian tsars-with special attention to Ivan III and Peter the Great-consisted of “winning in power through fraudulent employment of the enemy force, to weaken this force while using it and, finally, to destroy it after having used it as an instrument”.

In 1931, Stalin decided to give a twist to his policy of propaganda by establishing a new mystified history of Russia in which nothing less than “progressivism” of the policies of Tsarism and the messianic role of the Russian people represented by the conquests of their Tsars in Europe and the Far East was exalted.

As it could not be less, Stalin prohibited the publication of the book, although Marx’s own daughter, Eleanor, had softened it in 1899 to strip it of “Russophobia”. The book was first published in Spanish in 1979 by the publisher La banda de Moebius.