Eduardo González

In October 1883, the town council of Líjar, in Almería, declared war on France asking this country to apologize to King Alfonso XII, who had been treated with disdain during a visit of State in Paris. As in so many similar episodes (Huéscar, in Granada, and Móstoles, in Madrid, they maintained hostilities with France from the War of the Independence to the end of the 20th century), things did not go further and everything came to a picturesque war.

This story started in September 1883, when Alfonso XII arrived in France from, among other countries, Germany, whose recent unification at the expense, precisely, of Napoleon III had turned into an affront to the French pride.

In Germany, the great-great-grandfather of the current king did something diplomatically stupid, which was presiding parades and manoeuvres of the Prussian Armey and accepting the rank of colonel of the Uhlans, whose garrison was no less than in Strasbourg, the beautiful Alsatian city taken away from France by the German.

As was to be expected, Alfonso XII was not only received in France with deep coldness by the president of the Republic, Jules Grévy, but also with evident hostility by a big crowd that jeered at him screaming Death to the Uhlan and Long live the Republic.

Once in Spain, the king was subjected to two apologies: one in Madrid, where he was acclaimed and accompanied by the crowd to the Royal Palace, and the other one in Líjar, a town of Sierra de los Filabres whose Town Council, led by the mayor Miguel García Sáez, approved on 14 October 1883 a side in which he remembered that, during the War of the Independence, “an old and sickly woman, but daughter of Spain, had murdered herself thirty French that stayed at her house”.

With this precedent, the Town Council warned “the inhabitants of the French Territory” that the town of Líjar had “six hundred useful men” able, each of them, to defeat 10,000 French soldiers. After calculations (according to which, a young man at war is equivalent to 333.33 “sickly old women”), France would need six million soldiers if it wanted to win against Líjar.

The side included mentions to Sagunto, Bailén, Lepanto and Pavía, to figures such as Charles V (who “crossed France alone terrifying the World with his figure”) and Gonzalo of Córdoba and the “revenge and bravery” of those of Líjar “to make disappear from the map of continents the Coward French Nation”.

For all that, “the Town Council, taking into account what the mayor said, agrees by unanimity to declare war on the French Nation, addressing a statement to the president of the French Republic directly, and previously announcing to the Government of Spain this resolution”.

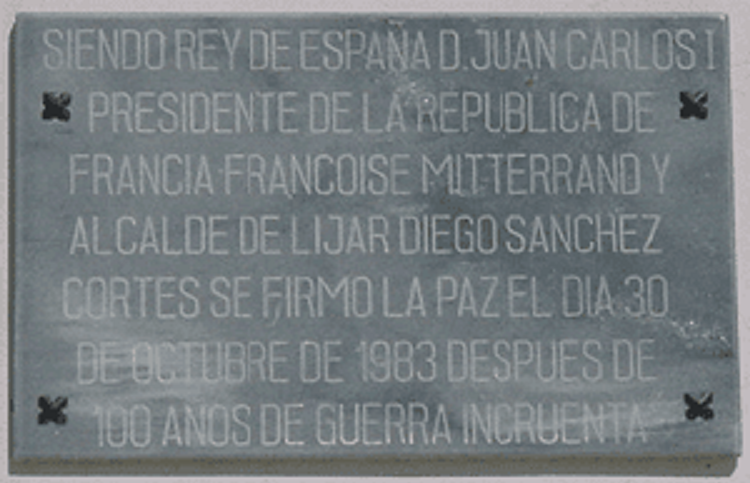

It did not come to much and, one hundred years later, on 30 October 1983, the peace was signed, in the presence of the political and military authorities of the opposing sides.