Eduardo González

On November 20, 1975, at 4:58 a.m., a young teletype operator at the Europa Press news agency named José Luis Blanco Mascañeras had the unexpected honor of being the first to break the news of the death of dictator Francisco Franco.

José Luis Blanco, a dear friend whom this writer knew very well, was one of those “all-rounders” who, in those days, often joined newsrooms very young, almost children, as apprentices willing to do anything.

José Luis, specifically, started at fourteen, and one of his first tasks was to travel by bicycle to the censorship offices to show them the texts and obtain their approval before they could be published. Apparently, the censors’ arguments for banning some of his texts were so utterly ridiculous that when he had to explain it in the newsroom, he was always the one who got the blame. “This kid’s stupid, he doesn’t understand anything,” they’d tell him. Then, when someone older tried to check if it was true, they discovered that the kid had understood absolutely everything.

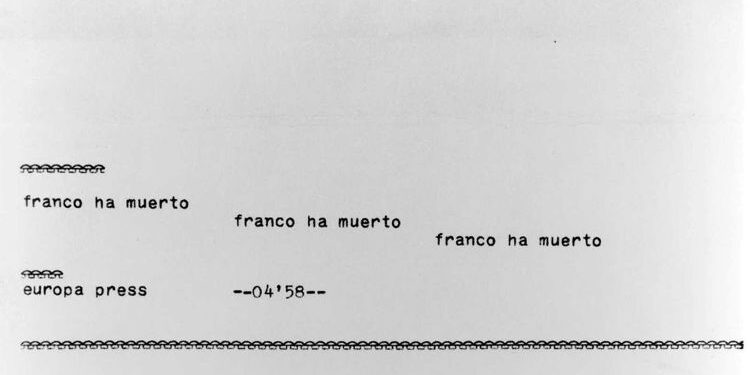

Aside from those early experiences, which gave him a good idea of how the dictatorship operated, a still young but much more experienced José Luis Blanco Mascañeras had the honor, years later, of going down in journalistic history for having been, in his humble position as a teletype operator, the person responsible for publicly transmitting the phrase “Franco is dead” (three times), which was true. Indeed, Franco had died.

Those events are masterfully recounted by another great veteran of Europa Press, Jesús Frías, editor-in-chief at the agency since 1976, in his book ‘From Europe to Europe. 30 Years of History Lived Since the News,’ published in 2012 by Palabra.

“I don’t know who knew the news first. Perhaps the first to find out was Franco himself or the doctors treating him, I don’t know. But the first news outlet to report Franco’s death was the Europa Press agency, and this is recognized worldwide and internationally. All the world’s news agencies—AFP, Associated Press, UPI, Reuters—reported the news, citing Europa Press,” Frías explained in an interview with ‘Daily Motion’.

Europa Press had prepared the entire operation in anticipation of the news and had several top-level sources (“wires”) who had committed to reporting Franco’s death or, at the very least, not to deny it if asked. “These people weren’t going to tell us that Franco had died, but they weren’t going to deceive us either,” primarily “to avoid speculation,” because “the news that Franco had died had been falsely reported several times by foreign news agencies,” Frías explained.

Among these sources were a military officer from the Prime Minister’s Intelligence Service, a friend of the Minister of Information and Tourism, León Herrera; Nicolás Franco y Pasqual de Pobil, the dictator’s nephew and a close friend of the agency’s president, José Mario Armero; and a member of the medical team that treated Franco.

“A large vehicle with very powerful lights”

In the early morning of November 20, 1975, only three journalists were awake at the news agency: Mariano González, stationed at La Paz Hospital in Madrid; Marcelino Martín Arrosagaray, who was on duty that night in the newsroom; the telephone operator Clemente Sanz Fernández; and José Luis Blanco.

Mariano González was among the numerous journalists, both Spanish and foreign, gathered at the hospital awaiting news, but he had decided to go outside for some fresh air to clear his head. It was then that he saw “a large vehicle with very powerful lights” enter the emergency room. A few minutes later, he saw another similar vehicle and, based on the license plates of both, suspected they belonged to the heads of Franco’s Military and Civil Households, a suspicion he was immediately able to confirm through a police officer.

The heads of the Military Household and the Civil Household used to visit the hospital every night until ten o’clock, and the fact that he saw them again a few hours later at such an unusual hour, entering through a “discreet” place (the Emergency Room), made him suspicious. “For them to return at that hour was very strange. I called the newsroom and told Marcelino,” explained Mariano González. The exact phrase was: “I think that Franco, if he hasn’t died, is about to die.”

“I have a telex ready saying that Franco is dead. If I publish it, am I way off?”

Immediately afterward, Marcelino Martín Arrosagaray made the rounds of calls to the established contacts. With all of them, he “bluffed, saying, ‘We know Franco has died,'” and both of them, especially the dictator’s nephew, implied that, indeed, he had died. The last call was to the Presidential Intelligence Service: “I have a telex ready saying that Franco is dead. If I publish it, am I way off?” he asked. The other person (a military officer) hesitated for a moment and said “no.”

Immediately afterward, Martín Arrosagaray woke the director of Europa Press, Antonio Herrero, in the middle of the night to fill him in on the details and ask for instructions. The director did the same with a source he himself had, whose identity he couldn’t reveal and whom he had promised to call only to verify if it was true that Franco was dead. Antonio Herrero’s next message was: “Publish it.”

José Luis Blanco, as he told some of us, wasn’t keen on publishing it before official confirmation, but that would mean missing out on the biggest scoop of all. “Publish it now, it’s the director’s order!” Marcelino Martín shouted at him. And, of course, José Luis obeyed and released the flash: “Franco is dead, Franco is dead, Franco is dead.” Three words, repeated three times in a staggered fashion, to dispel any doubt. It was 4:58 a.m. on November 20, 1975.

Obviously, they were dealing with a dictatorship, and while making a mistake on such a matter is serious in itself, in a dictatorship it was far more delicate. In fact, as Jesús Frías explained in the aforementioned interview, the reporters who were at Europa Press that night “were a little scared because, just as they were reporting the news flash of ‘Franco is dead,’ a statement came out from the Ministry of Information and Tourism saying: ‘The life of the Head of State is slowly fading away, but he still retains his vital signs.’”

The authorities had preferred to wait two or three hours before announcing the news in order to establish security measures, because “it was unknown what was going to happen.” “They didn’t want it to be known for several hours, and we broke that plan,” Frías explained. Shortly afterward, the minister, León Herrera, sent a letter to Europa Press to congratulate them and, at the same time, reproach them for having “stolen the story.” It wasn’t all so friendly: someone from the General Directorate of Press called the newsroom to warn them that they were going to “have to swallow the wire.”

Many years later, after more than fifty years at the agency and on the occasion of his retirement, José Luis Blanco Mascañeras received a framed reproduction of the historic wire from the then-director of Europa Press, Ángel Expósito.