Luis Ayllón

The diplomatic crisis with Israel unleashed after Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s trip to Israel and Palestine has broken the difficult balance that Spain has maintained for almost 38 years between the two sides of the conflict.

It was in January 1986 when Felipe González’s government dared to take the step that Israel had been waiting for since its creation as a state in 1948. The Franco regime, obsessed with what it considered to be Judaism’s links to Freemasonry and communism, did not want to recognise the new state and opted to throw itself into the hands of the Arab countries, relying on their support in order to join the United Nations.

The arrival of democracy in Spain did not bring about a rapid change of attitude either, although there was the occasional embrace between the Prime Minister, Adolfo Suárez, and the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), Yasser Arafat. Fear of a backlash from the Arab world prevented the Spanish authorities from taking the step of recognising the state of Israel.

With Spain’s entry into NATO and, later, its accession to the European Economic Community, Felipe González moved to establish diplomatic relations with Israel, a process carried out with great discretion and which culminated on 17 January 1986 in The Hague. The feared Arab reaction did not occur, beyond a few testimonial complaints.

In an attempt to silence these complaints, the government formalised the Statute of the PLO Office in Madrid, which eventually, when the Palestinian National Authority was created, became the General Delegation of Palestine in Spain.

This opened a new stage in Spain’s position in the Middle East, in which the Socialist government was able to move with great skill, to the point that 30 October and 1 November 1991 were marked as the dates on which Spain scored one of its most spectacular diplomatic successes by organising the Madrid Peace Conference.

The fact that the channels of relations with both Israel and the Arabs were open, together with the good relations forged by González with the then presidents of the United States, George Bush, and of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, were key elements for the US Secretary of State, James Baker, to call the Spanish Foreign Minister, Francisco Fernández Ordóñez, to propose the Spanish capital as the venue for a Peace Conference at which Israelis and Palestinians would sit down together for the first time.

The Madrid meeting, organised in less than a fortnight, brought together the heads of state and government of the United States, the USSR, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Jordan (whose delegation included the Palestinians, led by Yasser Arafat) and Israel. All of them were able to set in motion a peace plan that would later materialise in the Oslo Accords, which ultimately failed.

After that moment, Spain, under both the González and José María Aznar governments, continued to sail between Israeli and Arab waters. Exchanges of official visits with Israel proceeded normally. Shortly after the Madrid Conference, González travelled to Israel and years later, in 1995, he would go to Gaza. For his part, Aznar was in Israel in 1999 and met with Arafat on Palestinian soil, after Spain had financed the construction of the Gaza airport, which years later would be destroyed by Israeli bombing.

Also in 2009, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero travelled to Israel and Palestine as prime minister, something his successor, Mariano Rajoy, did not do.

It was in 2010 that Spain took an important step forward by raising the status of the Palestinian diplomatic representation in our country. It went from being a General Delegation to a Diplomatic Mission, with a head of representation with the status of ambassador and inclusion in the list of the Diplomatic Corps accredited in Spain on an equal footing with other foreign ambassadors. Spain already supported the two-state solution to try to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Exchanges of visits at the level of heads of state contributed significantly to maintaining this balanced position. In March 1992, 500 years after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain decreed by the Catholic Monarchs, Israeli President Haim Herzog travelled to Madrid and met with King Juan Carlos in the synagogue. A year later, Don Juan Carlos and Doña Sofía visited Israel on a first official trip in which the King defended the exchange of peace for land, paid tribute to the victims of Nazism and planted an olive tree in the Beit Shemesh forest as a symbol of peace.

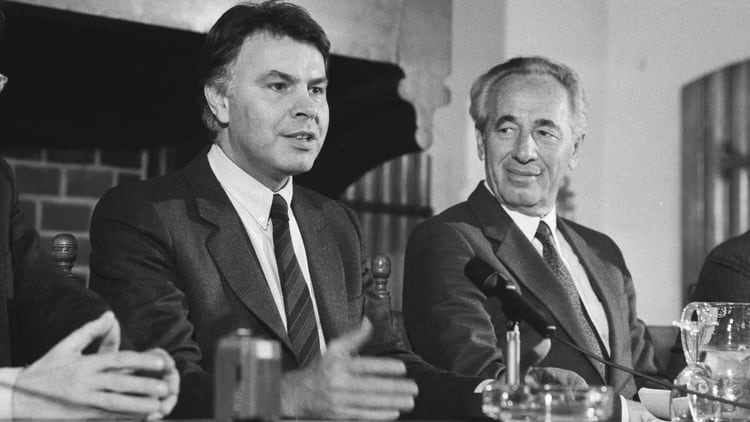

More recently, the celebration in 2011 of the 25th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and Spain prompted the Israeli President, Shimon Peres, to travel to Spain and, a few months later, the then Prince and Princess of Asturias Don Felipe and Doña Letizia made an official visit to Israel and also to Ramallah, where they were received by the President of the Palestinian National Authority, Mahmud Abbas.

In 2017, as King Felipe and Queen Letizia received a state visit to Spain by President Reuven Revlin, at a time when there was some unease in the Spanish government, then presided over by Rajoy, who considered that Israel had not been sufficiently clear in its rejection of Catalonia’s aspirations for independence.

A few years earlier, in 2014, a relevant event took place when all the parliamentary groups in the Congress of Deputies approved a resolution urging the government -which at that time belonged to the PP- to recognise the Palestinian state, but linking this move to the prior ‘negotiation process’ between Israelis and Palestinians, which would guarantee peace and security for both, respect for citizens’ rights and regional stability. It also called for ‘seeking, in any action in this regard, coordinated action in concert with the international community, and specifically with the European Union, taking fully into account the legitimate concerns, interests and aspirations of the State of Israel’.

Neither the government of Mariano Rajoy nor the subsequent government of Pedro Sánchez took any steps to implement this resolution.

In any case, in recent years, relations between Madrid and Tel Aviv were not the best, to the point that the Israeli government announced in 2017 that it was freezing its relations with Spain, after the United Nations Security Council, over which our country presided in 2016, passed a resolution condemning the Jewish settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

These incidents highlighted the fact that, beyond formally speaking of good relations between the two countries, the truth is that they were not very fluid from a political point of view. One fact is particularly striking: since 1998, when Netanyahu himself visited, no Israeli prime minister has officially visited Spain.

Nevertheless, economic exchanges have been growing, as have scientific and cultural exchanges, especially since the creation in 2010 of the Sepharad-Israel Centre in Madrid. Likewise, for a long time, Spanish intelligence services have collaborated fruitfully with the Israelis, who are considered to be among the best experts on the world of jihadist terrorism. That collaboration could now suffer, unless the waters are restored, which is difficult given that some of the ministers in Sumar’s quota publicly hold very radical positions vis-à-vis Israel.