Eduardo González

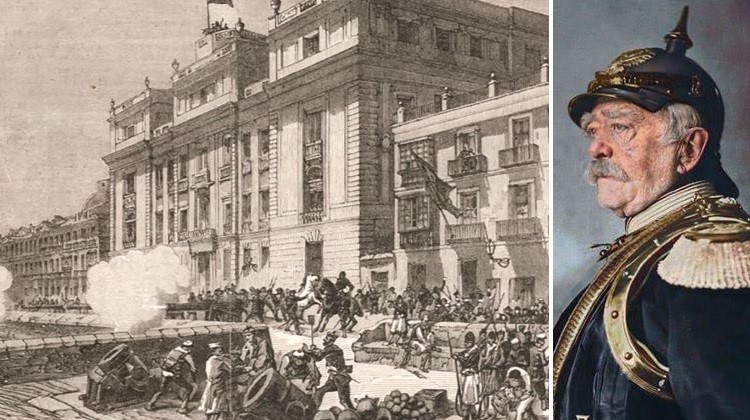

In July 1873, 150 years ago, Otto von Bismarck, chancellor and architect of the newborn German Empire, decided to send his ships to southeastern Spain to try to stop the cantonal uprising of Cartagena, a revolutionary and military uprising that precipitated the fall of the first Spanish Republic and that, in the opinion of the Iron Chancellor, could become a destabilizing focus for all of Europe.

In July 1873, a few months after the abdication of King Amadeo I and the proclamation of the first Spanish Republic (1873-1874), the so-called Committee of Public Salvation planned the uprising of the provinces to impose a Federal Republic “from below” without waiting for the Constituent Courts, elected in May of that year, to elaborate and approve the new Federal Constitution.

The revolt, which began on July 12 in Cartagena and spread to other cities, especially in the south and east, was brief and easily defeated because of the excesses and the lack of organization and coordination of the rebels. The exception was Murcia, where Antonio Gálvez Arce, Antonete, proclaimed the Cantón Murciano (Murcian Canton). From then on, with the support of the ships of the squadron, 15,000 men under arms and more than 500 artillery pieces, the heavily fortified city of Cartagena, naval base of the Navy and epicenter of the revolution, played the main role in the conflict from August until January 12, 1874, when it capitulated to the government forces.

In any case, the cantonalist revolt did not take place in a vacuum. As recalled by researcher Luis Álvarez Gutiérrez, of the Centro de Estudios Históricos del C.S.I. C, Madrid (“El marco internacional del Cantonalismo: el naciente Imperio alemán frente a Cartagena y el Cantón murciano”, Anales de Historia Contemporánea, 1994), the international context of the moment was conditioned, among other factors, by the recent formation of the German Empire after the Franco-Prussian war, which substantially modified the play of forces in Europe; the contemporary episode of the Paris Commune and its coincidence with the rise of the First Workers’ International (AIT), which awakened the fear of revolutionary contagion throughout the continent; the interest of Bismarckian diplomacy in what was happening in Spain since the “Glorious Revolution of 1868”, especially for its possible impact on the southern flank of its great rival, France; the growing rapprochement between the three central-eastern powers of Europe, Prussia, Austria and Russia, to deal with possible revolutionary upheavals; and the gradual rapprochement between the German Empire and Great Britain with a view to maintaining balance and preserving the general peace of Europe in the face of possible revolutionary outbreaks.

In these circumstances, the proclamation of the Republic in Spain (February 11, 1873) and its slide towards federalist forms raised, according to the researcher, not a few fears in the European chancelleries for the possible establishment of republican regimes in Portugal and Italy and for the eventuality of a unification between Portugal and Spain to form an Iberian Confederation with a revolutionary base.

Bismarck takes the initiative

In view of the not very reassuring news that the German diplomatic and consular representatives were sending to Berlin about the events in Spain, and with the argument of guaranteeing the security and economic interests of the German subjects residing in the peninsula, Otto von Bismarck decided to leave everything ready with a view to obtaining the approval of Emperor Wilhelm I for a possible military intervention in Spain in case of necessity. Therefore, in March 1873, he approached the head of the Imperial Admiralty, General Albrecht von Stosch, to ask him if he could count on some units of the Imperial Navy to send them to the Spanish coasts. In his reply, the admiral announced to the Iron Chancellor that he would send back to Europe the bulk of the naval forces sent to the Caribbean in order to have them available where and when it was considered appropriate.

Although the Spanish area in which the German naval forces were to be deployed was not specified, Bismarck decided to attend to the requests of some German colonies in the southeast of Spain, especially the Germanic merchants of Malaga, who demanded a naval expedition to the Mediterranean coasts because of the prevailing anarchy and with the argument that England, France and Italy had already done the same. With the emperor’s approval, Stosch ordered three ships to be sent to Malaga to “protect the German subjects and their goods in that city”. Thus began the German naval presence in Spanish waters, which was to lead to the later direct involvement of the German Empire in the Murcian Canton conflict.

At first, according to the aforementioned author, the German ships sailed the Spanish waters between Barcelona and Cadiz, stopping in Malaga and other ports to gather information on the public order problems caused by socio-political upheavals and insurrections. Thanks to these contacts, German consuls and naval commanders regularly informed Berlin about the links between the agitators and the ideas of the International and about their similarity with the Paris Commune of 1871, as demonstrated by the proclamation of a Commune in Seville.

The Murcian Canton

The initial calm collapsed on July 20, 1873, days after the beginning of the cantonal insurrection in Cartagena, when the Spanish Government declared as “pirate ships” the Navy vessels that had mutinied in favor of the revolutionaries and asked the governments of other countries to treat them as such. In these circumstances, Bismarck ordered the dispatch of a German squadron to Spain to intervene in the Murcian Canton revolt from a naval base of operations in Gibraltar, a decision that generated extensive diplomatic correspondence between the emperor, the Iron Chancellor, the German Foreign Office, the Admiralty, the diplomatic and consular representatives of the Empire in Spain and the German embassies and legations in London, St. Petersburg, Vienna, Rome, Lisbon, Brussels, The Hague, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Constantinople.

In compliance with the decree recently approved by the government of Nicolás Salmerón that declared as “pirates” all ships flying the red cantonal flag, the German frigate SMS Friedrich Carl intercepted on July 23rd the Spanish steamship Vigilante when it was about to enter Cartagena and the captain of the same German vessel demanded from the Junta de Cartagena, for the same reasons, the surrender of the frigate Vitoria. The Vigilante was sent to the base in Gibraltar for its later return to the government forces. The Murcian Canton then considered the possibility of declaring war on Germany because of the capture of this ship, but finally backed down because it considered that the operation had been carried out without Berlin’s permission.

In any case, in this whole operation (which contributed, in the medium term, to the defeat of the Murcian Canton), the German Government was very careful not to interfere in the struggles between the sides and ordered the naval units to maintain the strictest neutrality and to avoid any appearance of support for the Republican government in Madrid, which Bismarck considered as pernicious as the IWA itself because of its proximity to some important Republican and Socialist leaders in Europe, such as the Frenchman Léon Gambetta.

In any case, Germany did not act alone, but was even induced by the British Foreign Office to send the squadron (hence the center of operations in Gibraltar) and received a request for help from Portugal to stop the Spanish revolutionaries’ attempt to create an Iberian Confederation on a republican basis that would be attractive to the Portuguese revolutionaries themselves. Besides, Bismarck took into account the agreements between the emperors of Germany (Wilhelm I), Austria (Franz Joseph) and Russia (Alexander II) to put an end to the republican socialist movements, coming, above all, from France.

As if that were not enough, Bismarck was in the midst of a political conflict with the Catholic Church, which became particularly bitter in the spring of 1873.In those circumstances, the Chancellor did everything possible to stop the other great Spanish insurrection, although of very opposite sign to the cantonalist one: the Carlist War, whose victory would have strengthened the most ultramontane and Church-friendly sectors in Germany.

This factor, together with German suspicions that its great rival, France, supported the Carlists, encouraged the Chancellor to support the international recognition of General Francisco Serrano, who became President of the Government in January 1874, immediately after the coup d’état of General Manuel Pavía which put an end, in fact, to the Republic. Serrano put an end to the cantonalists in Cartagena (with the governments of France, Germany or Great Britain acting as intermediaries), defeated the Carlists in the siege of Bilbao in 1874 and brought about the restoration of the Bourbons, which was accelerated in December 1874 with the coup d’état of General Arsenio Martínez Campos.Bismarck’s plan for Spain had triumphed.