Eduardo González

Between the Cerro Almodóvar Park and the Vía Carpetana, in the Aluche neighbourhood in southwest Madrid, is the Leon V of Armenia Street. Likewise, very close to the Palacio de Santa Cruz, the headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, is the León V restaurant. In both cases, homage is paid to one of the most peculiar characters in the history of Madrid. Dethroned in 1375 by the Egyptian Mamluk, his desperate attempts to gather support to reconquer his kingdom led him to the current capital of Spain, where, between 1383 and 1391, he became the only feudal lord in the history of the Villa.

Leon remained no more than a few months in the Madrid Alcazar, setting of the current Royal Palace, before launching himself again to the adventure of re-gaining a throne that had been left vacant for ever. One of life’s coincidences; in the calle Mayor 81, next to the historical Almudena Cathedral and the Royal Palace, is located, since September 2010 the Armenian embassy, a small former Soviet republic, the territory of which only occupies a tiny piece of that kingdom, which in the year 301 a.c. proclaimed itself the first Christian confessional State in history, a decade before the conversion of the Emperor Constantine.

The preludes to the story of Leon V can be found in the XI century, when the Armenians who were escaping from the advancement of the Seljuq Turks, sought refuge in the southern coast of what is today Turkey, under the protection of the Byzantine Empire, and they founded the Armenian Principality of Cilicia. Little Armenia was born; and they maintained their Independence for nearly 300 years, in which, under the standard of Christianity as their national identity feature, they got involved in the great Western Crusades of the XII and XIII centuries.

The Crusades attracted numerous visitors to the country, among them the Lusignan, a powerful feudal family from the French Poitou, which the legends of the time said descended from the spirit Melusine, half woman, half snake. Between disasters and adventures, the Lusignan family became kings of Cyprus and Jerusalem at the end of the XII century, until in 1341, one of their descendants, Guido of Lusignan, rose to the Armenian throne as Constantine II.

Two more Constantines came and went before we arrive at our Leon V, a member of the Cypriot branch of the Lusignan family, who was crowned in September 1374 and whom, barely one year later, received the sad honour of becoming Armenia’s last king, after the Mamluk of the Sultan of Babylon (which is how the Spanish sources named the Egyptian Mamluk sultan) took over Sis, the capital of the kingdom.

Leon V, at 32 years old, refused to apostatize, which would have allowed him to remain on the throne, and was taken to Cairo as a prisoner, where he managed to make contact with some pilgrims who were on their way to the Holy Land and with their mediation he was able to ask the Christian princes for help. After turning to Pedro IV, the Ceremonious, of Aragon, Leon V’s emissaries were able to reach the Castilian king, Juan I, who committed himself to intercede on his behalf before the Sultan, and to sending a party to liberate the Armenian monarch.

Leon V received his freedom on September 1382, after which he began a voyage through Rhodes, Venice, Avignon (seat of the antipope Clement VII) and Barcelona, to try to garner, unsuccessfully, the material support necessary to reconquer his kingdom. In min-1383, his pilgrimage led him to Badajoz, where he was able to meet with the king of Castile, thanks to the help of his accomplice and interpreter Juan Dardel (Leon had absolutely no knowledge of any of the languages of the Spanish peninsula), a French Franciscan who was his main guardian during his captivity in Cairo.

The negotiations with Juan I about the recovery of the Armenian throne were as frustrating as all that had come before, but at least he was compensated with a very particular feudal concession. In October 1383, the bells of San Salvador church (situated before the current Plaza de la Villa) called together an extraordinary meeting of the Madrid Council. They were informed of the surprising decision, taken by Juan I, to award Leon V (according to what can be read in the Chronicle of Councillor Pero López de Ayala dominion over the Villa of Madrid, “for all his life (…) with all rights and rents”. The donation included, in addition, the localities of Andújar and Villarreal (today, Ciudad Real), with their respective rents, and a pension of 150,000 maravedíes.

Leon V was not chosen “King of Madrid”, as so many authors have repeated, following the initial error made by the chronicler Gil González Dávila in the XVII century, but it is true that he became the first and only feudal lord of the Villa, which, ever since its conquest by Alfonso VI in 1085 had always been royal land. During an extraordinary meeting, called by the tolling of the bells of St Salvador, the Madrid Council agreed, on the one hand, to accept King Juan I’s order to “pay homage to the King of Armenia” but on the other hand, expressed their discomfort for a concession that violated the city’s rights under the privileges of the fueros. In order to quieten the dissenting voices, the Spanish monarch agreed that, once Leon V passes away, Madrid would return to its former condition as royal land.

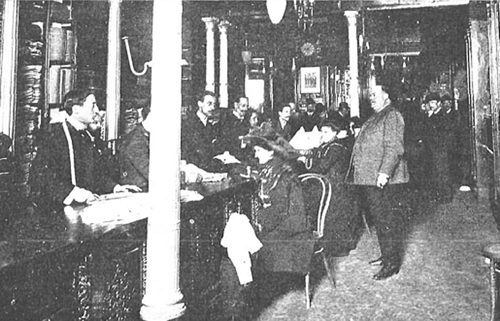

Leon V at the Alcazar

With the terms clarified, the exiled Armenian King settled down in the Alcazar, which was located within the grounds of what is today the Royal Palace, and ordered the reconstruction of the buildings towers, since they had been left severely damaged after a fire in times of Enrique II, first Trastámara king.

Despite the clichés, widespread even among the citizens of Madrid themselves, the Villa occupied a relatively important position within Castile. The Villa (not a “city” since the name was reserved for those places that had a cathedral) had 10,000 inhabitants (not a small figure for the times) and had been the seat of the Kingdom’s Cortes on a number of occasions, like those called in 1309 by Fernando IV or the ones celebrated in 1329 and 1341 by request of Alfonso X, calls which used to be accompanied by the concession of new privileges and exemptions for Madrid.

In 1346, Alfonso XI approved the creation of the Villa’s Regiment, for greater glory of the political ambitions of the urban oligarchy. From the accession to the throne of the Trastámara dynasty, the Castilian monarchs had frequently resided in the Madrid Alcazar, in which they propelled numerous reforms, and called new Cortes in 1390, 1393, 1419 and 1433. In the XY century, the Madrid Villa was included in the select group of 17 countries with a right to vote in the Castilian Cortes.

In any case, Leon V spent no more than a few months in Madrid (those of his first Winter). Obsessed by his desire to regain the Armenian throne, he began a new journey that took him to Navarra, to meet with Carlos the Bad, to Lleida to request aid from the king of Aragon, to Avignon to get to the Pope, and finally to Paris, where he met with the King of France, Charles VI. The outcome was as expected; in the midst of the XIV century crisis, with France caught up in their wars with England (Leon V even went so far to head an embassy from Charles VI to London to try to agree to a truce), Armenia was at the back of the queue.

From that moment, Leon V resided in France, the homeland of his Lusignan ancestors. He died in November 1393, at the Tournells Palace, in Paris, after which his cousin, the Cypriot king, Jacob I of Lusignan, went on to head a long list of unhappy pretenders to the Armenian throne. Leon was buried at the Convent of the Celestines, near to the Place de la Bastille, and on his tombstone he is named as Prince Leon of Lusignan, fifth Latin king of the kingdom of Armenia. His mortal remains were desecrated and lost for ever during the French Revolution, though his tomb was moved to the Saint-Denis basilica, on the outskirts of Paris.

After leaving Madrid, the King of Armenia only once returned to Castile; in February 1391, to attend Juan I’s funerals, celebrated in Toledo. In April of that same year, the Madrid Council were able to convince Enrique III (a twelve year old boy) to recognise that his father had made a mistake and, consequently, revoked the donation of the Villa. Leon V had been dethroned for the second time.