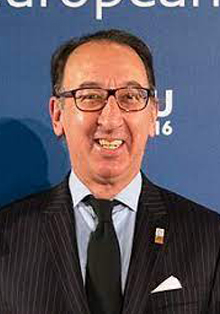

Carlos Malamud

Senior Analyst for Latin America at the Elcano Royal Institute

In the worldview of any self-respecting Mexican nationalist, and President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is today one of its main exponents, there are two black beasts. The first is Spain, which was demonised at the origin of the new nation and throughout the 19th century to cement the new national identity forged on the ruins of the Mexica empire. As Tomás Pérez Vejo has rightly pointed out: ‘In that myth of origin which is in essence all national history, and every nation, the [Spanish] conquest irremediably represented the death of Mexico at the hands of Spain’.

The second bête noire is the United States. In the mid-19th century, the neighbouring country took over several territories that had been part of the viceroyalty of New Spain: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Utah and parts of Kansas, Oklahoma and Wyoming. The territorial loss amounted to more than half the area of the Mexican state at the time. This was the beginning of a stormy relationship, marked by the tearfulness with which such a territorial amputation was experienced. This was also the origin of the famous phrase repeatedly attributed to Porfirio Díaz: “Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the United States”.

As a good populist politician, López Obrador, known as AMLO, finds in nationalism a vital tool to mobilise his followers. By touching a sentimental nerve that is easily manipulated, he manages to articulate a close bond of proximity and belonging between the leader and the masses. Now, the current leader could have chosen between the United States and Spain to concentrate his attacks on, but he chose Spain, why did he do so?

Although Spain is the second largest investor in Mexico, with almost 7,000 companies, and Mexico is the sixth largest investor in Spain, the relationship with the United States is much closer. Beyond the 38 million Mexicans who live there and the 3,180 kilometres of common border, the United States is the leading investor, the largest trading partner (it accounts for 80 per cent of Mexican foreign trade) and the source of most remittances. Hence López Obrador’s reverential fear of openly confronting his neighbours. The political repercussions of an economic deterioration would compromise his image and his ‘revolutionary’ project of the Fourth Transformation (4T).

Although there is much to lose with Spain, the outcome would be less catastrophic. On the basis of a simple cost/benefit calculation, the president, who is an experienced and calculating politician, chose his external enemy, although he prefers internal ones. It is his way of weakening his opponents and imposing his objectives. The list of those who have received the presidential rapapolvo is extensive: journalists, businessmen, the National Electoral Institute (INE), the UNAM, the trusts that finance cultural and research activity and many others.

Curiously, since 1977, when Mexico and Spain normalised their diplomatic relations, the bond between the two countries, regardless of the political colour of whoever headed each government, has been excellent. Until today, when despite two theoretically progressive governments (one with a marked populist bias), relations have deteriorated to levels unknown in the last 45 years. Even with Donald Trump López Obrador has behaved better than with Pedro Sánchez.

There is one final element that the Mexican president knows, and he plays on it. The ties between Mexico and Spain, between the Spanish people and the Mexican people, are so solid that they are not going to break easily despite so much nonsense. And if they deteriorate, they will quickly return to normal, once the obstacle that weighs them down has been overcome.

© All rights reserved