Eduardo González

Next March 13, the Minamata Convention on Mercury, the international agreement to protect human health and the environment from anthropogenic emissions and releases of mercury and its compounds, will enter into force for Spain.

The Minamata Convention – whose name recalls the serious health damage caused by untreated discharges into the sea by a petrochemical company in this Japanese bay during the 1950s and 1960s – regulates the use and releases of mercury (including supply, trade, storage and management of wastes and contaminated sites), prohibits the opening of new mercury mines and requires the closure of existing mines, among other measures.

The agreement was adopted in October 2013 in Kumamoto, Japan, under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and was signed on that date by 91 countries, including Spain. The agreement officially entered into force in August 2017 after being ratified by 50 countries. It has now been ratified by around 130 states and organizations. The European Union, as such, ratified the convention in May 2017 (with the only dissenting votes in the European Parliament from the French National Front), after which the Commission urged the pending member states to complete ratification.

Spain signed it ad referendum on October 10, 201, but it took until May 2021 for the Council of Ministers to approve its referral to the Cortes Generales and authorize the manifestation of Spain’s consent to be bound by that convention. After its passage through both Houses, King Philip VI issued the instrument of ratification on November 16. Finally, the agreement will enter into force for Spain on March 13, as published this week in the Official State Gazette (BOE).

On average, most EU states ratified the text around 2017. In contrast, Spain has been the last country in the Union to join the main international instrument against mercury emissions, after Poland, the penultimate on the list, ratified it in November last year. The European Union’s legislation on mercury already includes almost all the obligations set out in the Minamata Convention. Therefore, Spain has so far found itself in an anomalous situation, in which, on the one hand, it was already bound by most of the content of the convention through the EU but, on the other hand, it could not participate in its management due to its status as an observer country without voting rights at the Conference of the Parties.

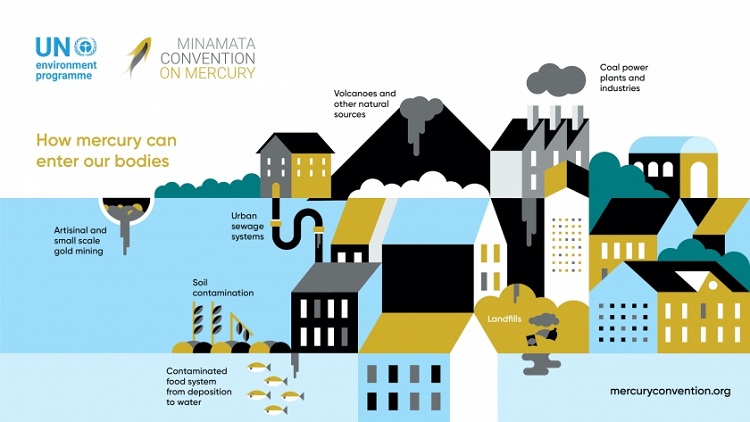

According to a report by the Carlos III Health Institute, Spain is the second country in the European Union with the highest mercury contamination in fish and the Spanish population has ten times more mercury in its blood than that of countries such as Germany, the United States or Canada. In Spain, the main sources of mercury pollution are coal-fired power plants and chlorine production plants. After becoming a State Party, Spain will be able to obtain financial and technical assistance to address mercury pollution and ensure controls on imports of mercury and mercury-added products, among other benefits.