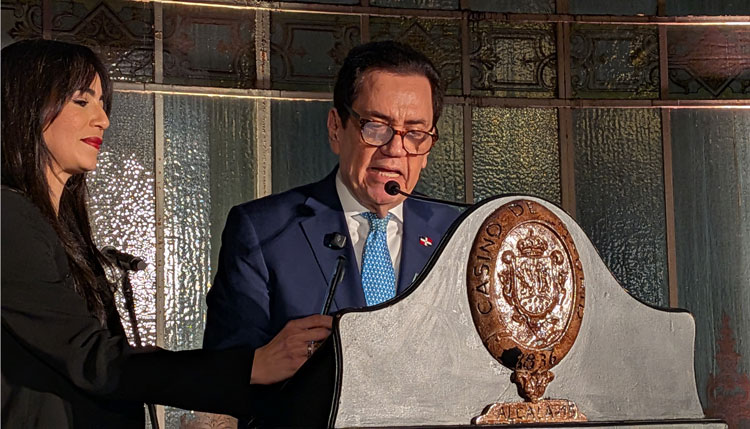

Ángel Collado

Pedro Sánchez’s government, after guaranteeing itself control of the legislature with the State Budget and in the midst of the opposition crisis, finds itself with an unexpected factor of internal instability: its vice-president Yolanda Díaz is campaigning to promote herself as a left-wing alternative to Sánchez himself.

From the cabinet of the social-communist coalition, the heiress of Pablo Iglesias is reformulating the political space of Podemos with a proposal for a new personal brand backed by the fact that she is the leader with the highest rating in the official CIS polls, ahead of the head of the Executive.

Díaz, affiliated to the Communist Party of Spain from a young age and with a long political career in Izquierda Unida before joining the lists of the Podemos conglomerate, has become the star of the cabinet with a cultivated image opposed to that of her mentor Iglesias. In the PSOE they have gone from relief at the departure from government of the founder of the left-wing populist movement to concern over the rise of the Minister of Labour who has now become vice-president by personal appointment of Iglesias himself. And that concern has turned into indignation among the socialists at seeing Yolanda Díaz disassociate herself from Sánchez’s management of the origin of the pandemic by disregarding all the warnings.

The minister not only removes a taboo subject for the head of the Executive, as was the decision not to take any measures in March 2020 until the feminist marches on the 8th were held and the number of cases of infection multiplied throughout Spain. She also leaves for use in the next election campaign the forgotten fact that she did get down to work in February and proposed protocols for action in companies to prevent the spread of the coronavirus to trade unions and employers.

Díaz has already claimed as her personal achievements the most positive or best-selling actions of the coalition government, such as the so-called social peace thanks to her understanding with the trade unions, the increase in the minimum wage and even job creation. Now she is distancing herself from Sánchez’s first major failure at the start of the pandemic and making it clear that in the next elections she will compete with the PSOE for the electoral space of the left as a whole, not just for the most extreme “little corner”, according to her own definition.

The minister’s objective is as obvious as her weapons to achieve it, as she promotes herself from within the government as being responsible for what might turn out well or prove popular (the next is the labour counter-reform) and denies the failures of the Executive.

The vice-president is also beginning to take advantage of Sánchez’s commitment to feminism as a fundamental message of his government. She surrounds herself with the main leaders of the far left, such as the mayor of Barcelona (Ada Colau), the vice-president of the autonomous government of the Valencian Community (Mónica Oltra) and the head of the opposition in the Community of Madrid (Mónica García) to prepare an electoral brand of her own to succeed the burnt-out United We Can. In terms of reclaiming the more feminist left-wing vote, Díaz has the fundamental quality that Sánchez cannot compete with, namely that of being a woman.

The socialists’ unease with Yolanda Díaz is justified by the government’s polls. Sánchez needed Podemos’ 35 seats to be sworn in as president after the November 2019 elections. Iglesias thus brought the fruit of the 13 per cent of citizens’ votes he won in the elections. Once in the cabinet as vice-president, he continued to lose support in the polls. There were polls that left Podemos below 10 per cent.

Díaz’s emergence as the main representative of the communist sector of the government changed the trend, and in the CIS barometer of last November, the intention to vote for the extreme left was already a few tenths of a percent higher than the real results of two years earlier. The start of the vice-president’s campaign gave almost two points to the podemites and their rise was partly at the expense of the PSOE’s attrition.

The party led by Pedro Sánchez and the party created by Pablo Iglesias have shared the same electorate for years. In the 2016 elections they shared the votes of the left almost equally, with just a point and a half advantage for the Socialists. Already in power after the 2018 motion of censure against Mariano Rajoy, the PSOE was clearly ahead of Podemos.

The concern now for the PSOE is that its main partner in the government, which is also a competitor in the polls, may steal their thunder in the government from the left, and then steal their votes in the elections. This is Yolanda Díaz’s plan.