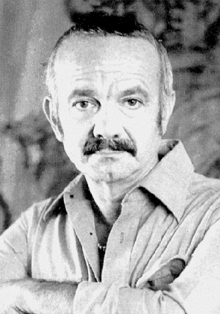

Frédéric Mertens de Wilmars

Professor of International Relations at the European University of Valencia

Is Europe bound to a “Polexit” in the short term? Many leaders, commentators and political analysts have been saying so since the Polish Constitutional Court on 7 October affirmed the prevalence of the Polish constitution over the EU legal order.

On the other hand, such authoritarian decisions by the ultra-conservative Polish government are neither new nor surprising, and have led to several crises between Warsaw and Brussels. In this regard, we should not forget that the European Commission has initiated sanction proceedings against Poland for violating the rule of law. And the position of the Polish high court reflects the collusion between the political power and the judiciary, where more than 50% of its members have been appointed by the ruling PiS party.

However, no one dares to comment on the PiS party’s intentions regarding Poland’s de facto exit from the EU. The former President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, believes that although the current ruling party does not want to provoke a “Polexit”, its attitude could unintentionally lead to such a situation, as it did during the initial Brexit process. Thus, some conservatives assert their constant hostility to the European Union, while other, majority members of the same political group reject the transfer of national competences envisaged by the EU’s functioning in the name of Polish sovereignty.

In reality, the PiS position should be understood as a differentiated management of the Polish state’s EU membership obligations. The government is not unaware that more than 80 percent of the population is pro-EU. Nor are they unaware that Poland benefits from substantial European subsidies and that they expose themselves to political – and electoral – risks by questioning them for maintaining an attitude contrary to the EU’s core values. Moreover, in the recent conflict between Poland and Belarus over refugees blocked at the country’s eastern border, the Polish government is aware of the international and domestic political benefits it can gain from EU support.

Therefore, rather than proceeding with outright opposition, Warsaw has chosen to launch a series of tests to assess the strength of its positions. The continued firmness of the European Commission and all member states – with the exception of Hungary – and the absence of a Eurosceptic tendency in Polish public opinion preclude direct confrontation with the EU. However, the Polish government is closely following the situation in other European states where a political trend is emerging that is openly in favour of a “Europe of nations”, i.e. a dismantling of European institutions.

Beyond the internal dimension, this Polish crisis raises the legal questioning of the heart of the EU system: the prevalence of European rules over national norms. In the absence of a European constitution – rejected in 2005 – Poland’s decision creates a precedent that other Eurosceptic states such as Hungary could use. Refuting the binding nature of the European Union, including all of its rules, entails non-recognition of the EU itself. After Brexit, the European institutions, the chancelleries of the member states, and also all European market operators, see in the legal snub of the Polish Constitutional Court the serious risk of a breach in the functioning of the EU; which in turn weakens the positioning of the EU in its relations with other international powers such as Russia, China and the United States.

© All rights reserved