Eduardo González

On 18 January 1871, 150 years ago, the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles was the scene and witness to the disappearance of the last embers of Napoleon III’s operetta Empire and the birth of the German Empire. This event, which represented a radical change in the European geopolitical panorama, was the result of a devastating war, the Franco-Prussian War, which had its origins in Spain.

The Franco-Prussian War was, above all, the final straw that allowed Otto von Bismarck to seal the unification of Germany. To achieve this, the Prussian Iron Chancellor only needed to provoke the weak and easily provoked French Emperor Napoleon III, whom he managed to drag into a suicidal war in 1870. To complete the plot, a casus belli was needed and Bismarck found it in the most unsuspected place: Spain.

The first steps in this story were taken in 1868 with the revolutionary overthrow of Queen Elizabeth II in Spain. Amidst strong republican sentiments, the Spanish Parliament, like those of other countries, opted in 1869 to seek a new king to prevent the situation from becoming too revolutionary. As everyone knows, the chosen one was Amadeo of Savoy, son of the first king of unified Italy and the first and last Spanish king to be elected by parliamentary vote. Amadeo I only lasted two years on the throne, before escaping from that “cage of madmen” called Spain, in his own words.

However, before Amadeo’s election there were other candidates. One of them, supported by the Unionists, was the Duke of Montpensier, husband of the Infanta Luisa Fernanda, who was openly opposed by Napoleon III because he did not want a member of the House of Orleans as King of Spain and whose candidacy finally fell apart after he killed his cousin, the Infant Henry, in a duel. Another candidate, in this case of the progressives, was the King of Portugal, Ferdinand of Coburg, who rejected an offer that seemed to him, above all, to be an attempt by Spain to annex his country.

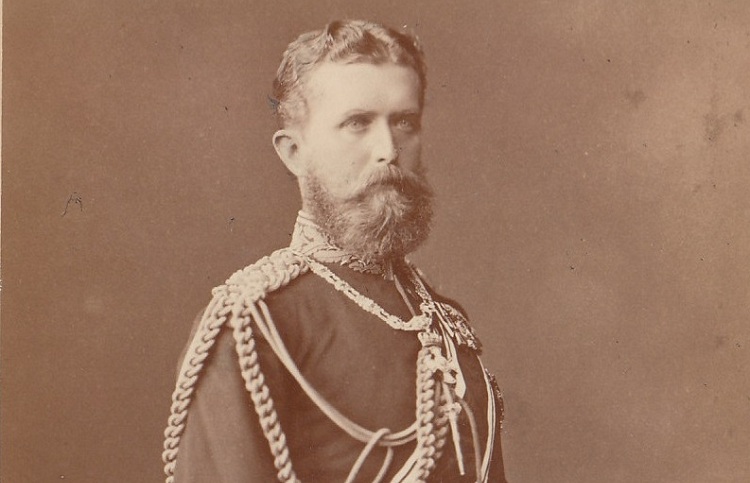

The third candidate was the German Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, who didn’t win the jackpot either but became the great protagonist of this story.

As expected, Napoleon III openly opposed the candidacy of the German, whom he rightly saw as the great asset of the King of Prussia, William I (Leopold’s cousin), to encircle France. Thanks to pressure from French diplomacy, Charles Anthony of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, Leopold’s father, promised to renounce the Spanish throne on behalf of his son, but Napoleon III was not satisfied and demanded that William I clearly and blatantly disavow Hohenzollern’s candidacy.

To this end, the Count of Benedetti, the French Ambassador to Berlin, went to the German spa town of Bad Ems to convey this message to William. As the Prussian monarch himself reported, the French ambassador behaved in an “impertinent manner” and broke all the rules of protocol to demand that he refrain from supporting the candidacy of Hohenzollern. Offended, the King not only objected outright to his requests, but also refused to receive Benedetti again, to whom he communicated, through an aide de camp, that “His Majesty had nothing more to say to the ambassador”.

The Ems Telegram

This diplomatic incident fell on fertile ground. On the one hand, Napoleon III was very weakened in his own country and felt that a war would do him a lot of good to calm down the revolutionary mood at home. On the other hand, Bismarck wanted a new war (he had just defeated Denmark) to unite all German territories definitively around a single cause, but he did not want to be the one to declare war. The Iron Chancellor therefore decided to provoke the French Emperor, for whomever it was that took the wrong step, and Napoleon III finally accepted the decoy thanks to Bismarck’s skilful handling of a historical document: the so-called Ems Telegram.

In the telegram, the King of Prussia not only explained to the chancellor the unpleasant incident he had just had with the French ambassador, but also authorised him to make its contents public. Bismarck did so by means of a press release, but not before skilfully modifying the text to make it look like a humiliation to the French ambassador and an offence to the honour of France. Everything else came in cascade: the French press heated up, the streets of Berlin and Paris were filled with nationalist demonstrations and on 19 July 1870 Napoleon III declared war on Prussia.

The war was a disaster for France and led to the popular overthrow of Napoleon III in September 1870. On 18 January 1871, William was proclaimed Kaiser of the new German Empire in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles. Ten days later, the Government of National Defence of the French Third Republic signed the armistice, which not only meant a humiliating defeat for France, but also gave way to the definitive unification of Germany and the birth of an Empire (Reich) which, with over 40 million inhabitants and a vertiginous economic growth, was to become the first power in Europe.

All this had begun, if only in the role of a comparsa, in a medium-sized power like Spain, which in the following years experienced a Republic, a coup d’état and a Bourbon restoration in the person of Alphons XII.